Running D&D horror one-shot:

A Practical Guide for DMs

Horror is the genre that D&D DMs most want to run and most consistently get wrong. The problem isn’t ambition — it’s that horror requires fundamentally different techniques than standard fantasy adventure. The same tools that make combat encounters exciting actively undermine horror. Bright torch-lit rooms, clearly statted enemies, and confident heroes who wade into danger by default are the opposite of what horror needs to function.

But when it works, horror D&D produces sessions that players remember for years. The tension, the dread, the genuine surprise when something goes wrong — these are experiences that standard dungeon crawls simply can’t replicate. This guide covers the practical techniques that make D&D horror actually scary, from atmosphere and pacing to encounter design and the genres that play best at the tabletop.

This article is part of our Complete Guide to Running D&D for Small Groups. Horror is one of the genres that works best with small parties of 2-3 players — and we’ll explain exactly why.

Why Horror Works Better With Small Groups

Horror depends on vulnerability. Characters need to feel threatened, isolated, and uncertain. A party of six heavily armed adventurers with three healing spells between them doesn’t feel vulnerable — it feels like an assault team. The power fantasy that makes D&D exciting in standard play actively prevents horror from landing.

Small groups solve this at the structural level. Two or three characters have fewer hit points, fewer resources, and fewer tactical options. They can’t cover every skill, can’t absorb sustained damage, and can’t rely on strength in numbers. The vulnerability that horror requires is built into the party composition rather than artificially imposed through DM fiat.

Atmosphere also scales inversely with group size. Horror relies on silence, tension, and dread — moods that shatter the moment someone cracks a joke or starts a side conversation. With two or three players, the table is quiet enough for atmosphere to build. Every sound effect lands. Every long pause carries weight. The DM can modulate tension with pacing and voice in ways that a table of six cross-talking players simply doesn’t allow.

This is why every horror adventure we publish at Anvil & Ink is designed for 2-3 players. Not because we can’t scale up, but because horror at its best is intimate — and intimacy requires a small table.

Atmosphere: The Foundation of Horror

Before you think about monsters, encounters, or plot, you need atmosphere. Atmosphere is what separates “you fight a zombie” from “something is dragging itself toward you in the darkness, and it sounds like it used to be a person.” Same monster. Entirely different experience.

Environmental Storytelling

Horror environments tell stories through what’s wrong. A village where every window is boarded from the inside. A dungeon where the traps are pointed inward — designed to keep something in, not adventurers out. A forest where the birds have stopped singing and the trees are all bent in the same direction, as if pushed by something massive that passed through.

These details cost nothing to prepare. They’re single sentences dropped into your narration that signal to players that something is deeply, fundamentally wrong with this place. The key is specificity — not “the village seems abandoned” but “there’s a half-eaten meal on the table, still warm, and the chair is overturned.” Specific details activate imagination in ways that general descriptions never do.

Sensory Deprivation

D&D players rely on information to make decisions. Horror works by restricting that information. Limit visibility — torchlight reaches twenty feet, and beyond that is absolute darkness. Restrict what they can hear — their own footsteps echo so loudly they can’t tell if something else is moving. Remove their reliable tools — the compass spins randomly, the map doesn’t match the corridors, the sending spell returns only static.

When players can’t trust their senses, every decision becomes uncertain. That uncertainty is the emotional foundation of horror. They don’t need to see the monster to be afraid of it. They need to know something is there and not know what it is or where it’s coming from.

Physical Atmosphere at the Table

Dim the lights. Play ambient sound — dripping water, distant thunder, wind through stone corridors. Speak more quietly than usual so players lean in. These table-level adjustments sound simple, but they transform the play experience. When the room itself feels different, the fiction becomes more immersive. Players who would laugh off a zombie in bright fluorescent lighting feel genuine unease when that same zombie is described in a dimly lit room with a wind sound effect playing in the background.

Horror Subgenres That Work in D&D

Not all horror translates equally well to tabletop play. Some subgenres leverage D&D’s strengths; others fight against them.

Body Horror

Body horror — the corruption, transformation, or violation of the physical body — works devastatingly well in D&D because characters are defined by their physical capabilities. A fighter whose sword arm begins changing into something inhuman faces a horror that’s simultaneously narrative and mechanical. Body horror is visceral, specific, and impossible to ignore.

The Colossus Autopsy builds an entire adventure around body horror. Players explore the decaying anatomy of a 60-foot storm giant — navigating through organs, blood vessels, and biological systems that are simultaneously dungeon rooms and a corpse. It’s designed for adult players seeking genuinely unsettling imagery combined with tactical exploration and moral complexity.

Survival Horror

Survival horror — where resources are scarce and the primary goal is staying alive rather than defeating the threat — maps perfectly onto D&D’s resource management systems. Spell slots become precious. Hit points are irreplaceable. Every torch, every ration, every arrow represents a decision about what matters most right now.

Little Lambs captures this subgenre precisely. Street kids lured into a pit beneath the city with something massive and hungry moving in the darkness. Resources are minimal, escape routes are limited, and survival depends on clever use of environment rather than combat prowess. The vulnerability of the characters — level 2, minimal equipment — makes every threat feel overwhelming without requiring inflated monster statistics.

Creeping Dread

Creeping dread is horror that builds gradually. Nothing overtly terrifying happens in the first scene, or the second. But small wrongnesses accumulate — an NPC who repeats themselves without realizing it, a room that’s slightly smaller than it should be, a shadow that moves independently of its source. By the time the overt threat reveals itself, players are already unsettled.

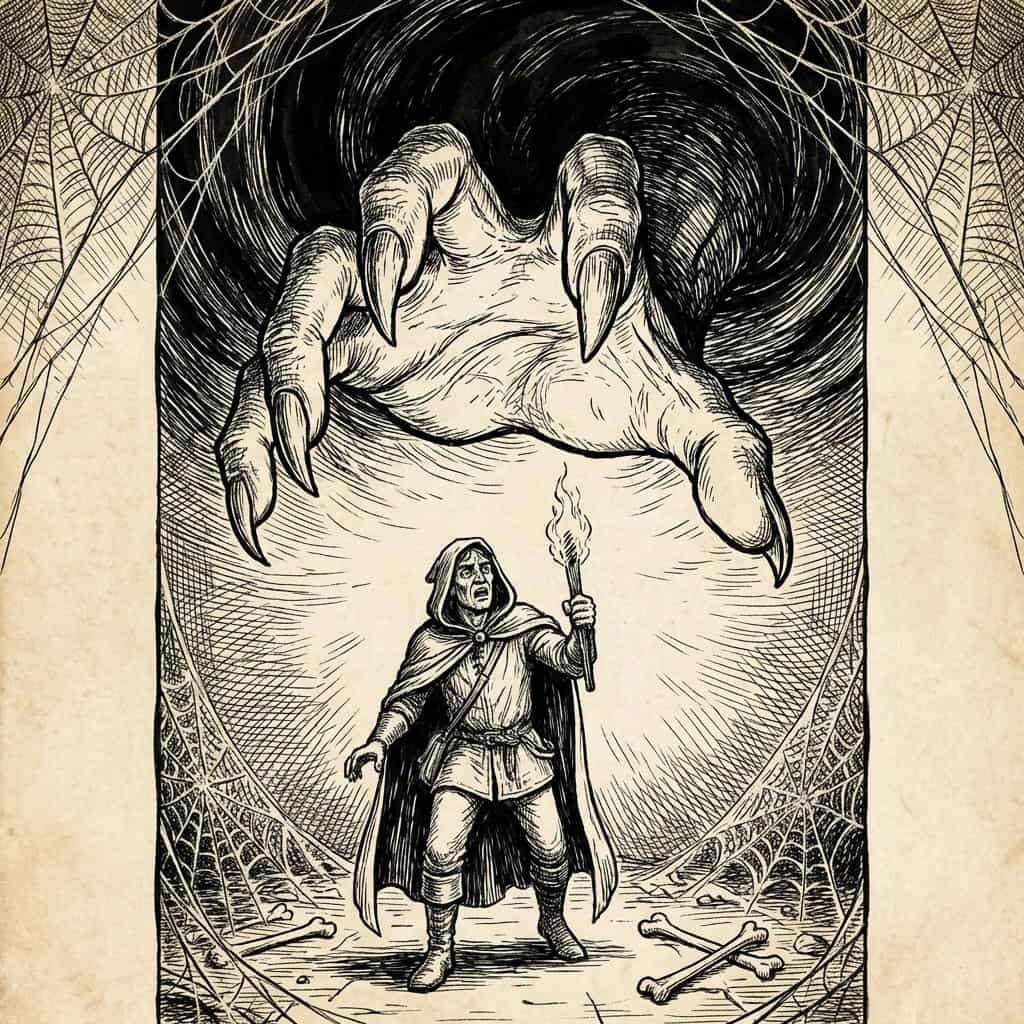

The Spider’s Seminary uses creeping dread to tremendous effect. The heroes killed the spider-goddess — someone else did, actually, and got all the glory — but they forgot to burn the eggs. Now those eggs are hatching, and someone expendable has to go clean up the mess. The horror isn’t the spiders themselves. It’s the growing realization of how many there are, how deep the infestation goes, and how unprepared your party is for what they’ve walked into.

Isolation Horror

Isolation horror works when characters are cut off from help, escape, or communication. The dungeon entrance collapses behind them. The blizzard makes travel impossible. The island is surrounded by waters that destroy boats. When there’s nowhere to run and no one to call, every encounter carries the weight of permanence — this is it, whatever happens here is what happens, and nobody’s coming to save you.

Frostfall combines isolation with survival horror in frozen wilderness. After an airship crash, the party treks through a hostile landscape with a guide who’s hiding a terrible secret. The isolation is environmental — blinding snow, freezing cold, no shelter — and the horror grows from the realization that the person you’re trusting might be the most dangerous thing out here.

Monster Design for Horror

Standard D&D monsters aren’t scary. Players who’ve fought fifty goblins aren’t afraid of goblin number fifty-one. Horror monsters need to break expectations — to behave in ways the rules don’t predict and players can’t optimize against.

Less Is More

The scariest monster is the one players never fully see. Describe sounds, smells, and traces — claw marks, slime trails, the sound of breathing from somewhere close. Let players build the threat in their imagination, which will always produce something more personally terrifying than anything you describe in full.

When the monster finally appears, keep the description brief and focused on one horrifying detail. Not a paragraph of anatomy — one image that sticks. “It moves on too many legs.” “Its mouth opens sideways.” “It’s wearing a face you recognize.” One specific, wrong detail is more effective than a thousand words of generic monster description.

Monsters That Break Rules

Horror monsters should do things players don’t expect from the D&D framework. A creature immune to a damage type that shouldn’t be possible. An enemy that gets stronger when hit. Something that phases through walls, ignores armor class, or targets saving throws that characters usually dump. When the rules stop being reliable, players lose the mechanical confidence that undermines horror.

Use this sparingly. One rule-breaking element per monster is enough. If everything about the creature is unusual, it becomes a puzzle to solve rather than a threat to fear. One impossible element surrounded by otherwise normal combat mechanics is far more unsettling than a completely alien stat block.

Monsters With Intelligence

Stupid monsters are obstacles. Intelligent monsters are terrifying. An enemy that watches the party, learns their patterns, and adapts its approach creates the feeling of being hunted rather than facing a random encounter. Have the monster avoid the fighter and target the spellcaster. Let it retreat when injured and return later, now prepared for the party’s tactics. Let it take something — a piece of equipment, a ration, a light source — while they sleep.

Intelligent monsters transform horror from a series of encounters into a sustained campaign of tension. Every dark corridor might contain something that’s been watching them, learning them, and waiting for the right moment.

Pacing Horror Sessions

Horror pacing is opposite to standard D&D pacing. Where action adventures build toward bigger and faster encounters, horror builds toward stillness and dread, punctuated by brief explosions of violence or revelation.

The Tension Curve

Structure your horror session as a tension curve that builds in three phases. Phase one is normalcy disrupted — something wrong is noticed, the mission begins, and the environment starts to feel off. Phase two is escalation — the wrongness intensifies, resources deplete, and the threat becomes more present without fully revealing itself. Phase three is confrontation — the full horror is revealed and must be faced, fled from, or survived.

Between phases, include brief releases of tension. A moment of safety, a dark joke that earns a nervous laugh, a room where nothing bad happens and players can catch their breath. These releases are essential — sustained maximum tension produces numbness, not fear. You need valleys to make the peaks feel high.

Let Players Scare Themselves

The most effective horror technique requires the least DM effort: silence. After describing something ominous, stop talking. Let the pause stretch. Players will fill the silence with their own speculation, and their imagined threats will be worse than anything you planned. “You hear a sound from the next room. It stops when you stop walking.” Then say nothing. Watch them terrify each other with theories about what’s in that room.

Safety at the Horror Table

Horror content requires more deliberate safety tools than standard D&D. Before running a horror session, discuss boundaries with your players. What types of horror are they comfortable with? Are there specific phobias, triggers, or themes they want to avoid?

Lines and veils are the simplest framework. Lines are topics that won’t appear at all. Veils are topics that can be referenced but happen “off-screen” without graphic description. Establish these before play, and respect them absolutely during play. Horror that makes players genuinely uncomfortable in ways they didn’t consent to isn’t good horror — it’s a violation of trust that damages the gaming relationship.

For groups playing with younger participants, or groups uncertain about their horror tolerance, consider “gateway horror” — adventures that create tension and spooky atmosphere without graphic content. The small group adventure design principles in our main guide include notes on scaling content intensity for different audiences.

Horror Beyond Combat: Investigation, Escape, and Moral Dread

The most common mistake in horror D&D is making it all about fighting scary things. Combat is the least scary part of D&D because it’s the most mechanical. The moment initiative is rolled, players shift from frightened characters to tactical optimizers calculating damage per round. Horror lives in the spaces between combat — in investigation, exploration, and the moments when players must choose between bad options.

Investigation horror asks players to understand the threat before confronting it. What happened here? Why are the villagers acting strangely? What’s behind the locked door that someone clearly doesn’t want opened? Every answer raises worse questions, and the investigation itself becomes a source of dread as the picture gets clearer. The Mystery Adventure Toolkit provides investigation frameworks that pair naturally with horror scenarios — the same clue-design principles that make mysteries work also make horror investigations compelling.

Escape horror reverses the standard adventure structure. Instead of progressing deeper into danger, players are trying to get out. The dungeon entrance collapsed. The fog is closing in. The ship is sinking. Every wrong turn, every locked door, every dead end raises the stakes because the threat is behind them and getting closer. Escape scenarios produce some of the most intense sessions in D&D because the goal is primal — survive and get out — and every failure has immediate, visible consequences.

Moral horror presents choices where every option costs something precious. Save the village but sacrifice the innocent prisoner. Destroy the artifact but condemn the person bound to it. Let the monster live because killing it means something worse gets released. These aren’t combat encounters — they’re ethical confrontations that leave players genuinely unsettled, not because something was gross or scary, but because they had to make a choice they’re not sure was right.

Your First D&D horror one-shot Session

Ready to run horror? Start simple. Pick an isolated location — a mine, a manor, a ship at sea. Add one wrong thing that escalates — strange sounds that get closer, rooms that rearrange themselves, an NPC who starts acting strangely. Build to a single confrontation with a monster the players have been dreading for the entire session.

Dim the lights. Play ambient sound. Speak quietly. Pause more than you think you should. Let your players’ imaginations do the heavy lifting, and you’ll discover that horror D&D is not only possible — it’s unforgettable.

For a ready-to-run horror experience, The Spider’s Seminary, The Colossus Autopsy, and Little Lambs each deliver distinct horror subgenres designed specifically for small groups. No rebalancing, no adaptation — just darkness, dread, and decisions that matter.

Horror that actually scares your players. Small-group adventures built for tension, dread, and impossible choices. Explore the dark side of the Ready Adventure Series at anvilnink.com.