Goblin Player Adventures in D&D: Flip the Script and Play the Monsters

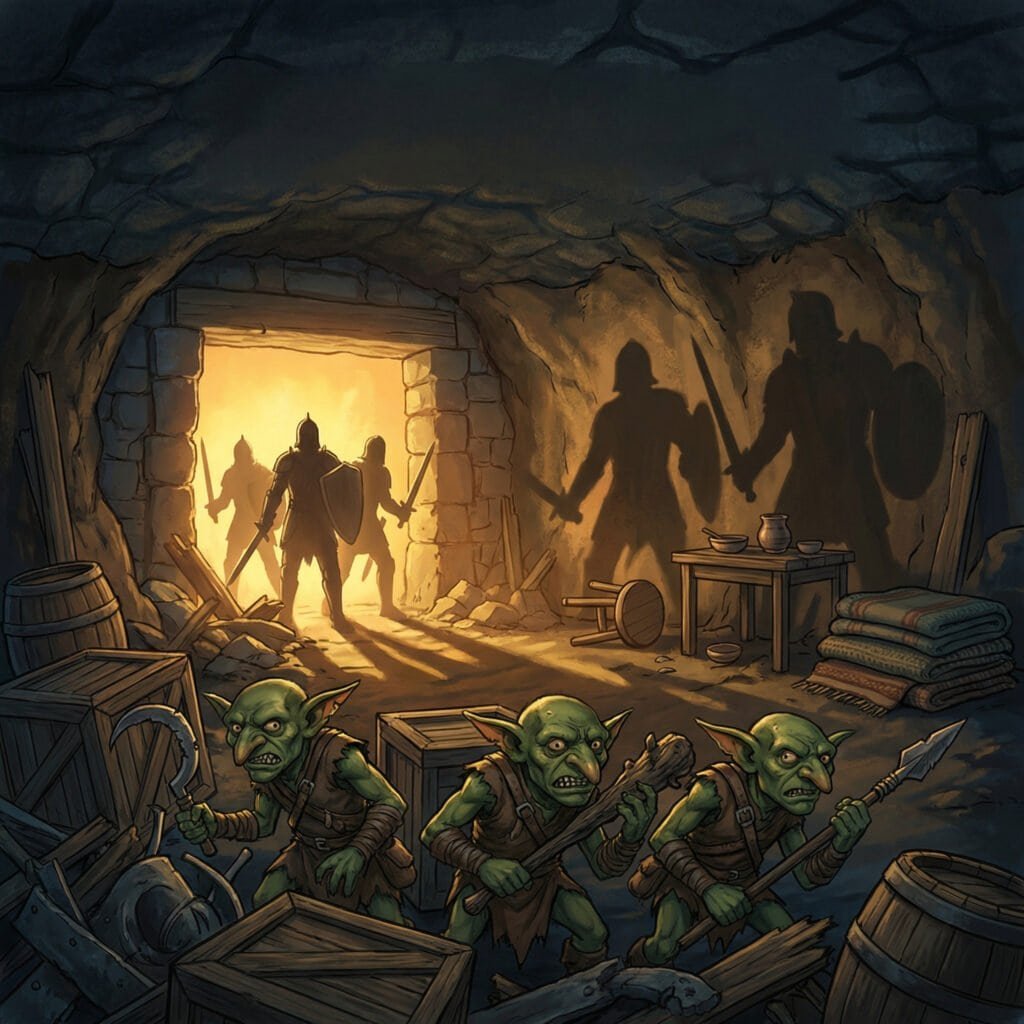

You’ve kicked down countless dungeon doors. You’ve slaughtered goblin tribes by the dozen. You’ve looted their meager treasures and moved on without a second thought. But what if the door stayed shut? What if you were the one trying to keep it closed? Goblin player adventures in D&D flip the script on traditional gameplay, transforming players from invading heroes into desperate defenders fighting for their homes.

Playing as goblins isn’t just a novelty—it’s a genuinely different D&D experience. The power dynamic reverses completely. Tactics change when you’re the weaker force defending territory rather than the stronger force invading it. Roleplay opportunities shift when your characters are society’s monsters rather than its heroes. Everything players take for granted gets questioned when they’re on the other side of the dungeon door.

This guide explores goblin player adventures in D&D and the broader concept of monster-perspective gaming. We’ll cover why these adventures create unique experiences, how to run them effectively, what makes goblin defenders different from typical adventurers, and ready-to-play adventures that deliver the monster perspective without requiring you to design from scratch.

Why Play as Goblins?

Monster-perspective adventures offer experiences that hero-based D&D cannot replicate. Understanding these unique elements helps you appreciate what goblin adventures provide.

The Underdog Experience

Traditional D&D positions players as competent heroes facing appropriate challenges. Even difficult encounters assume players can win with good tactics and decent luck. The fundamental assumption is player victory through superior capability.

Goblins invert this assumption. Against standard adventuring parties, goblins are outmatched. They have lower hit points, weaker attacks, inferior equipment. Victory requires cleverness, preparation, and exploiting every possible advantage. The underdog experience creates tension that power-fantasy adventures lack.

This tension produces different satisfactions. Defeating a dragon feels heroic. Repelling adventurers as goblins feels miraculous. Both are victories, but they resonate differently. The underdog victory carries emotional weight that expected triumph cannot match.

Moral Perspective Shift

When players play heroes raiding goblin caves, the morality seems clear. Heroes good, monsters bad. Treasure belongs to whoever can take it. The goblins were probably doing something evil anyway.

Playing as goblins complicates this narrative. The “treasure” is your tribe’s life savings. The “dungeon” is your home. The “monsters” are your family and friends. Suddenly, the adventurers breaking down the door aren’t heroes—they’re invaders committing violence against your community for profit.

This perspective shift doesn’t require declaring adventurers evil. It simply humanizes (goblinizes?) creatures players normally treat as obstacles. The moral complexity enriches gameplay without demanding particular conclusions.

Creative Problem Solving

Goblins can’t solve problems the way adventurers do. They lack the magical resources, combat prowess, and social standing that typical parties possess. This limitation forces creativity.

Traps become essential rather than optional. Terrain advantages matter more when individual combat favors enemies. Social solutions—negotiation, deception, misdirection—offer paths that fighting cannot. Players must think differently, which produces different gameplay.

The Other Side of the Door: Monster Defense Done Right

The Other Side of the Door provides the definitive goblin player adventure in D&D. The premise captures everything that makes monster-perspective play compelling: players become goblin defenders protecting their warren from invading adventurers, while the DM finally gets to play too—controlling a party of heroes storming the players’ home to steal their treasure.

Tower Defense Meets Tabletop

The adventure combines tower defense strategy with tabletop roleplaying. Players position their goblin defenders, set traps, and choose where to make stands. The approaching adventurers follow patterns players can anticipate and counter—but the adventurers are dangerous enough that mistakes prove costly.

This hybrid format creates unique gameplay. Strategic positioning matters session-long, not just encounter-by-encounter. Resource allocation across multiple defense points forces prioritization. The adventure feels different from standard D&D because it is different—a distinct format within the same rules framework.

The DM Gets to Play

One of the adventure’s most innovative features: the DM controls the adventuring party. For DMs who spend every session running monsters and NPCs, finally playing heroic characters—even as antagonists—provides refreshing variety.

This role reversal creates interesting dynamics. The DM knows player tactics from years of observation. Players know monster behavior from years of fighting them. Both sides bring meta-knowledge that creates surprisingly sophisticated play.

Multiple Victory Conditions

Survival isn’t the only goal. Players might defeat the adventurers outright. They might negotiate a truce. They might facilitate the adventurers’ departure with minimal losses. They might sacrifice treasure to preserve lives. Multiple valid outcomes prevent the adventure from becoming a simple combat grind.

These varied victory conditions support different playstyles. Combat-focused groups can fight to the last goblin. Roleplay-focused groups can attempt diplomatic solutions. The adventure accommodates rather than constrains player preferences.

Running Goblin Adventures Effectively

Monster-perspective adventures require adjusted DM techniques. These approaches help goblin games succeed.

Embrace the Tone

Goblin adventures naturally tend toward dark comedy. The absurdity of goblins defending against heroes, the desperate schemes, the unexpected victories—these elements lend themselves to humor alongside tension.

Embrace this tone rather than fighting it. Goblins can be simultaneously sympathetic and ridiculous. Their traps can be both clever and absurd. The adventure can matter emotionally while also being genuinely funny. These tones coexist naturally in goblin stories.

Make Goblins Individuals

When players encounter goblins as enemies, individual characterization is unnecessary. When players play goblins, each one needs personality. Even minor NPCs in the warren should have names, quirks, and relationships. This investment makes the stakes real.

Encourage players to develop their goblin characters beyond combat statistics. What’s their role in the warren? Who do they care about? What do they dream of? These details transform generic monsters into protagonists worth rooting for.

The Adventurers Should Be Scary

For the adventure to work, the invading adventurers must feel genuinely threatening. These aren’t the bumbling heroes of comedy—they’re competent warriors who outclass individual goblins significantly.

Describe the adventurers with the same menace you’d use for dragons or demons. Their approach should create dread. Their capabilities should intimidate. The fear is justified; these invaders can absolutely destroy the warren if the defense fails.

Reward Clever Defense

Goblins win through cleverness, not power. Reward creative defensive solutions generously. The trap that collapses the corridor should work. The distraction that divides the adventurers should succeed. The negotiation attempt should receive fair hearing.

When players invest creativity in their defense, validate that investment. Nothing kills goblin-adventure engagement faster than clever plans failing arbitrarily. The adventure’s premise promises that underdogs can win through wit—deliver on that promise.

Goblin Character Creation

Creating goblin characters requires different considerations than standard adventurer creation.

Embracing Limitations

Goblins are small, weak, and disrespected. Rather than minimizing these traits, lean into them. A goblin character concept should incorporate their limitations as features, not bugs.

The goblin who’s survived despite weakness has stories to tell. The goblin who’s earned respect in a hostile world has accomplishments worth celebrating. Limitations create character depth when embraced rather than ignored.

Community Connections

Goblins are intensely communal. Individual goblins exist within tribal structures, family groups, and social hierarchies. Character creation should establish these connections—who matters to this goblin, what role do they play, what obligations do they hold?

These connections provide motivation beyond personal survival. The goblin fighting to protect their family fights harder than one fighting only for themselves. Community stakes raise personal stakes.

Specialized Roles

Goblin warrens divide labor. Some goblins trap-make. Others scout. Some lead; others follow. Some fight; others support. Character roles within the warren structure provide identity beyond generic “goblin warrior.”

Consider what this particular goblin contributes to the community. Their role shapes their skills, relationships, and self-image. A trap-maker approaches problems differently than a scout does.

Beyond Goblins: Other Monster Perspectives

The monster-perspective concept extends beyond goblins. Other creatures offer their own unique experiences.

Kobolds: Trap Masters

Kobolds share goblins’ underdog status but emphasize traps and engineering even more strongly. Kobold adventures might focus on elaborate defensive mechanisms—Rube Goldberg deathtraps, environmental hazards, mechanical wonders built from salvage.

The kobold aesthetic differs from goblins too. Where goblins are chaotic and opportunistic, kobolds are methodical and devoted (especially to dragons). Different monster cultures create different adventure tones.

Orcs: Warrior Culture

Orcs offer less underdog dynamic but explore themes of honor, warfare, and cultural conflict. Orc adventures might involve tribal politics, battles against prejudice, or the tension between traditional ways and changing times.

Playing orcs works best when the campaign engages with their culture seriously rather than using them as simple brutes. Depth creates engagement; stereotypes create boredom.

Undead: Existence Questions

Undead perspectives raise existential questions. What does it mean to exist without life? How do undead regard the living? What purposes drive creatures for whom survival is irrelevant?

These adventures tend toward philosophical horror or dark comedy depending on approach. The undead perspective is inherently strange, which creates opportunities for genuinely alien viewpoints.

Integrating Monster Perspectives Into Campaigns

Goblin player adventures in D&D work as one-shots, but the perspective can also enrich ongoing campaigns.

One-Shot Interludes

When regular campaign sessions aren’t possible—missing players, schedule disruptions, DM needing a break—monster one-shots provide entertaining alternatives. The tonal shift refreshes everyone without disrupting campaign continuity.

These interludes might connect to the main campaign. The goblins players defend against adventurers today might be the goblins their regular characters encounter next week. Experiencing both perspectives deepens understanding of the game world.

Campaign Consequences

Actions in monster sessions can affect main campaigns. Perhaps the goblin warren players defended becomes a recurring location. Perhaps an NPC from the goblin perspective appears when regular characters visit the region. These connections reward engagement with alternative perspectives.

Moral Complexity Enhancement

After playing monsters, regular adventuring feels different. Players who’ve experienced being on the receiving end of dungeon raids may approach future raids with more nuance. The moral simplicity of “kill monsters, take treasure” becomes harder to maintain.

This complexity isn’t mandatory. Some groups prefer uncomplicated heroism. But for groups seeking depth, monster perspective provides it naturally.

Common Concerns About Monster Play

Some players hesitate about monster-perspective adventures. These concerns deserve consideration.

“Won’t It Be Too Silly?”

Goblin adventures often include comedy, but they needn’t be purely silly. The humor can coexist with genuine stakes, emotional investment, and meaningful choices. Tone is controllable—you can run goblins seriously if your group prefers.

That said, embracing some absurdity often produces the best results. Fighting against the format’s natural humor requires effort that might be better spent enjoying it.

“Is It Still D&D?”

Mechanically, monster-perspective adventures use standard D&D rules. Goblins have stats, make ability checks, and engage in combat using familiar systems. The perspective changes, but the game remains recognizably D&D.

The different experience doesn’t mean worse experience. Variety within a familiar framework often enhances appreciation of that framework. Playing goblins can make returning to heroes feel fresh rather than routine.

“Won’t the Power Imbalance Be Frustrating?”

The power imbalance is the point. Adventures like The Other Side of the Door are designed around this imbalance, providing goblins with tools—traps, terrain, numbers, desperation—that compensate for individual weakness.

Frustration comes from unfair imbalance, not imbalance itself. When the adventure accounts for goblin limitations and provides legitimate paths to success, the underdog experience becomes exciting rather than frustrating.

Getting Started with Goblin Adventures

Ready to put players on the other side of the dungeon door? These steps help you begin.

Start with a One-Shot

Test the format before committing to extended play. A single goblin session reveals whether your group enjoys monster perspective without requiring major investment. If it works, expand; if not, return to standard play with minimal disruption.

The Other Side of the Door provides an ideal entry point—complete adventure, tested mechanics, everything needed to run immediately. The adventure specifically addresses first-time monster-perspective play.

Discuss Expectations

Talk with players before the session. Monster perspective is different; some players need mental adjustment. Explain the adventure’s concept, discuss the tone you’re aiming for, and establish that this is meant to be fun despite (or because of) the inverted power dynamic.

Player buy-in matters more for experimental formats than for standard adventures. Ensure everyone’s on board before beginning.

Commit to the Bit

Half-hearted monster perspective produces half-hearted results. If you’re running goblins, be goblins. Make the warren feel like home. Make the adventurers feel like invaders. Make the stakes—defending family, community, existence—feel real.

Full commitment creates memorable experiences. Tentative execution creates forgettable ones. Choose to make it matter.

Conclusion: Defend Your Warren

Goblin player adventures in D&D transform familiar gameplay into something genuinely new. The perspective shift creates underdog tension, moral complexity, and creative problem-solving that hero-focused adventures cannot replicate. For groups seeking variety within the D&D framework, monster perspective delivers.

The Other Side of the Door provides everything needed to experience goblin defense immediately—tower defense gameplay, role-reversed DM experience, and complete adventure structure. For DMs who’ve spent years running monsters and want to try the other side, for players who’ve kicked down countless doors and want to hold one shut, the adventure delivers.

The heroes are coming. The door won’t hold forever. But you’re a goblin—and goblins survive through cleverness, desperation, and sheer stubborn refusal to die quietly.

They think you’re just another dungeon to clear. Prove them wrong. Defend your home. Show them what goblins can do when they’re fighting for everything they have.