Encounter Balancing for 2-3 Players Without the Math

The Challenge Rating system is broken for small groups. It assumes four players, a balanced party composition, and encounter pacing that rarely matches how small tables actually play. If you’ve ever plugged numbers into a CR calculator, built what should be a “medium” encounter for your two-player group, and watched it either steamroll the party or collapse in a single round — you already know the math doesn’t work.

The good news is you don’t need the math. Encounter balancing for 2-3 players is less about calculations and more about design philosophy. The DMs who consistently run great small-group combat have abandoned CR charts entirely in favor of principles that produce exciting, challenging, and survivable fights every time.

This guide covers those principles. It’s part of our Complete Guide to Running D&D for Small Groups, which covers adventure design, roleplay, and session structure for tables of 2-3 players.

Why CR Doesn’t Work for Small Groups

The Challenge Rating system was designed with a specific model in mind: four adventurers, balanced across roles, facing six to eight encounters per adventuring day with two short rests between them. Almost nobody plays this way — and small groups deviate from the model furthest of all.

The core issue is action economy. In D&D, the side with more actions per round has a massive advantage. Four players against four goblins is a fair fight. Two players against four goblins is a bloodbath — not because each goblin is too strong, but because the goblins collectively act twice as often as the party. CR doesn’t account for this disparity at smaller party sizes because it was never designed to.

Resource attrition is the second failure point. CR assumes characters will burn through spell slots, hit dice, and class features across a full adventuring day. Small groups playing one-shots or short sessions often face just two or three encounters total. Characters either have too many resources for the challenge (making fights trivial) or too few if the DM overcompensates (making fights lethal). The pacing model that CR depends on simply doesn’t apply.

The solution isn’t to fix CR. It’s to replace it with something that actually works for your table.

The Environment Is Your Best Encounter Tool

The single most effective change you can make to small-group encounter design is shifting complexity from enemy count to environment. Instead of asking “how many monsters should I use?” ask “what makes this location dangerous and interesting?”

Terrain That Forces Decisions

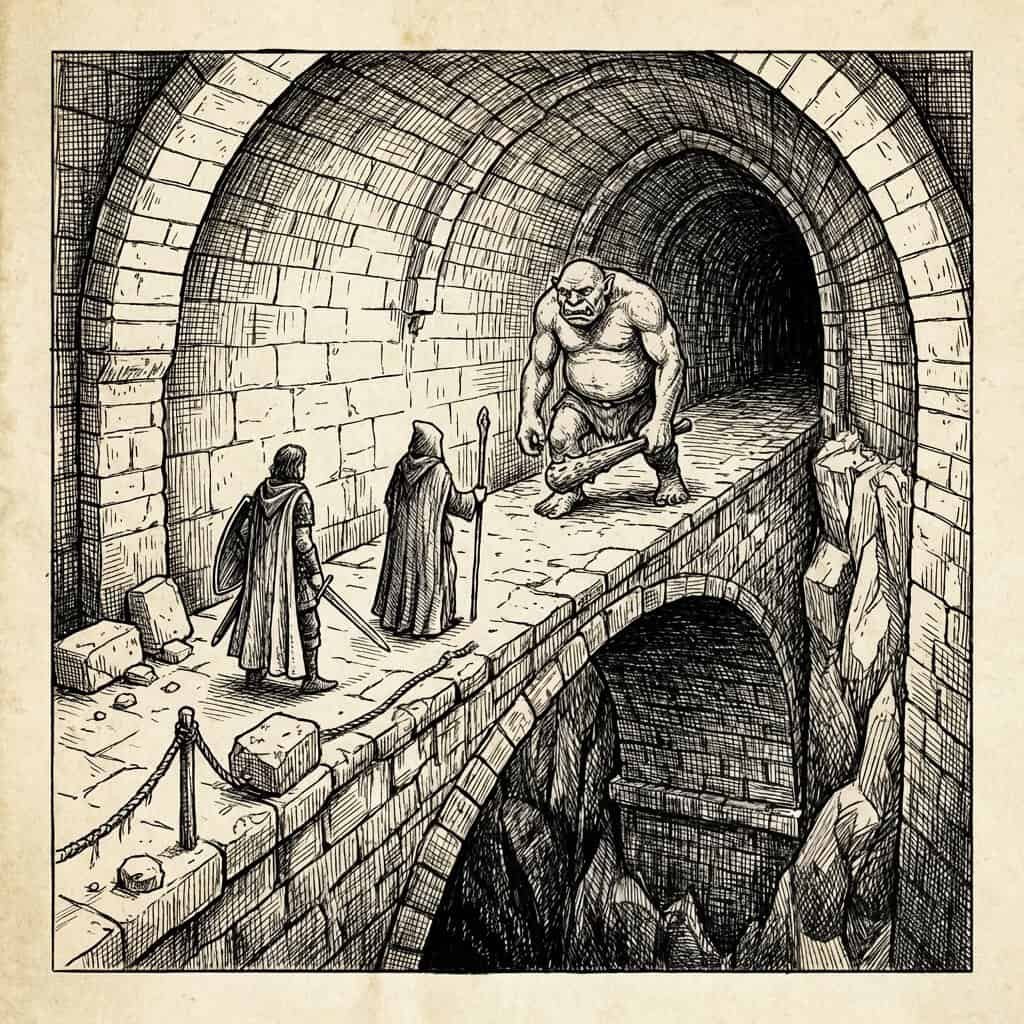

Every encounter location should include at least one terrain feature that creates meaningful tactical choices. A narrow bridge forces single-file movement and prevents flanking. Waist-deep water halves movement speed and makes ranged attacks from higher ground devastating. Crumbling platforms that collapse under weight turn a static fight into a mobile puzzle where standing still is as dangerous as the enemies.

These features don’t require additional stat blocks, preparation, or mechanical complexity. You decide the terrain effect on the spot — “the ice cracks when you step on it, roll Dexterity to keep your footing” — and suddenly a fight against two enemies feels as tactically rich as a full-party encounter against six. The terrain fills the mechanical space that missing party members would normally occupy.

Hazards That Escalate

Static hazards are good. Escalating hazards are better. A room on fire is dangerous. A room where the fire spreads one square per round is a ticking clock that transforms every combat round into a resource management decision. Do you spend your action attacking, or do you move to avoid the flames? Do you hold position for a better attack next round, or retreat to safety now?

Escalating hazards naturally limit encounter length — a critical advantage for small groups. Without escalation, a two-player party fighting a single tough enemy can devolve into an endless exchange of hits. With a room flooding, a ceiling collapsing, or poison gas spreading, the fight has a built-in timer that prevents stalemates and keeps tension rising regardless of how the combat dice fall.

The Sinking Tower of Hours builds this principle into its entire structure. A wizard’s tower literally sinking into magical sand creates escalating environmental pressure across five levels — each floor more dangerous and more compressed than the last. The environment does most of the heavy lifting, which is exactly how small-group encounters should work.

Fewer Enemies, More Interesting Enemies

The reflex when balancing for small groups is to reduce enemy count. That’s correct — but insufficient. Fewer enemies only works if each remaining enemy is individually interesting enough to sustain the encounter.

Give Every Enemy a Gimmick

A goblin with a shortbow is forgettable. A goblin that cuts ropes to drop chandeliers on the party, then ducks behind cover, is memorable. When you reduce enemy count, increase each enemy’s tactical vocabulary. Give them one unique behavior — an environmental interaction, a defensive trick, a retreat condition — that makes fighting them a puzzle rather than a hit-point race.

This doesn’t mean complex stat blocks. A goblin that uses the environment is mechanically identical to a standard goblin. The difference is entirely in how you run them. Describe the goblin kicking a barrel of oil across the floor toward the torch. Narrate the hobgoblin shouting commands that visibly boost goblin morale. These behavioral details cost zero prep time and transform encounters from arithmetic into storytelling.

Boss Fights With Phases

Single-enemy boss fights are ideal for small groups because they solve the action economy problem from the other direction — one enemy means the party isn’t outnumbered. But a single enemy with one set of behaviors becomes predictable after two rounds.

Design bosses with two or three phases. At full health, the ogre fights recklessly, charging and swinging. At half health, it becomes cautious — retreating to a defensive position, throwing furniture, calling for help. At quarter health, it’s desperate — fighting with savage fury or attempting to flee or negotiate. Each phase changes the tactical situation enough that the fight stays dynamic across its full length.

Lair actions are another tool for solo bosses. The room itself acts on a separate initiative count — a gust of wind from a broken window, a tremor that cracks the floor, magical darkness that extinguishes torches. These environmental interruptions give the boss effectively more actions per round without adding more enemies, keeping the action economy balanced against a small party.

The Three-Encounter Session Structure

Small groups work best with three encounters per session, each serving a distinct purpose. This structure provides enough variety and resource drain to feel challenging without the attrition grind that CR’s six-to-eight encounter model demands.

Encounter One: The Introduction

Your opening encounter should be winnable but informative. It establishes the session’s tone, introduces the primary threat or environment, and lets players warm up their abilities. Difficulty should be moderate — challenging enough to require some resource expenditure but not so punishing that characters start the session wounded and depleted.

Encounter Two: The Complication

The middle encounter changes something. The enemies fight differently than expected. The environment shifts. An ally turns. A new threat emerges. This encounter should be harder than the first and force players to adapt their approach. Resource management becomes real here — players who burned everything in encounter one feel the pressure, while conservative players are rewarded.

Encounter Three: The Climax

The final encounter is the session’s centerpiece. It should combine everything — the toughest enemy, the most dangerous environment, and a meaningful decision point. This is where boss phases, escalating hazards, and narrative stakes converge. Players should feel they earned the victory through tactical choices across all three encounters, not just the last one.

This three-encounter structure is the backbone of every adventure in the Ready Adventure Series. Each adventure is paced for 2-3 hour sessions with small groups, using escalating challenge and environmental complexity rather than enemy count to create tension.

Practical Balancing Shortcuts

When you need to build or adjust an encounter on the fly, these shortcuts produce balanced results without any calculation.

The Mirror Method

Make the enemy group a dark mirror of the party. Two players? Two enemies. Three players? Two enemies and one lieutenant. The enemies should roughly match the party’s capabilities — similar hit points, similar damage output, similar action options. This approach produces fights that feel fair because they functionally are fair. Neither side has an inherent action economy advantage.

The twist comes from asymmetry. The enemies have home field advantage, a hostage, or environmental control. The party has versatility, healing, and player creativity. Even mirror encounters feel distinct when the circumstances differ.

The Dial Method

Start encounters slightly easier than you think they should be, then adjust mid-fight using four invisible dials. Enemy hit points can quietly increase or decrease — if the fight is too easy, that ogre has twenty more hit points than you originally decided. Reinforcements can arrive — or not — depending on pacing. Environmental hazards can escalate faster or slower. And enemy tactics can shift from dumb to smart or vice versa.

These adjustments are invisible to players. They don’t know the ogre’s “real” hit points. They don’t know whether the reinforcements were planned or improvised. What they experience is a fight that felt dangerous, required smart play, and ended at just the right moment. That’s encounter balance — not a number on a chart, but a feeling at the table.

The Retreat Rule

Enemies should retreat, surrender, or flee when they’re clearly losing. This is both realistic and mechanically beneficial for small groups. Intelligent enemies who run when outmatched prevent the “cleanup round” problem where the last two goblins deal chip damage for three boring rounds. It also creates narrative opportunities — the fleeing enemy warns others, the surrendering bandit provides information, the retreating beast leads them to its lair.

Build this into your encounter design philosophy and your small-group sessions will feel tighter and more narratively satisfying. The Crimson Ceremony uses this principle throughout — enemies respond to the party’s investigation quality, retreating or escalating based on how much the players have discovered, creating encounters that feel reactive rather than preset.

Handling the “Glass Cannon” Problem

Small parties are glass cannons. Two characters can dish out significant damage per round but can’t absorb much punishment. A single critical hit from a tough enemy can drop a character in one shot, and with only one ally available for healing or stabilization, unconsciousness is far more dangerous than in a full party.

Address this through adventure design rather than mechanical patches. Provide environmental cover — pillars, overturned tables, alcoves — that allows characters to break line of sight and recover. Include potions, scrolls, and healing opportunities within the adventure itself rather than relying on party composition. Design encounters where enemies have reasons to not focus-fire a single character — multiple objectives, distractions, or behavioral programming that spreads aggression.

Short rests become critical for small groups. Build natural rest points into your sessions — a barricaded room after a fight, a hidden alcove in the dungeon, a moment of calm between crises. These breathing spaces allow characters to recover hit dice and short-rest abilities, keeping the party viable across multiple encounters without the full adventuring day pacing that CR expects.

Moral Complexity as Encounter Design

Not every encounter needs to be resolved through combat, and small groups often prefer non-combat solutions when they’re available. Moral complexity — where the “right” answer isn’t obvious and every choice has consequences — is itself an encounter design tool.

An enemy who can be reasoned with doubles the encounter’s complexity without adding a single stat block. A hostage situation where combat risks the hostage’s life creates tension that pure combat can’t match. A sympathetic antagonist who believes they’re doing the right thing forces players to question whether fighting is even the correct approach.

This philosophy is central to our “unsung heroes” design approach at Anvil & Ink Publishing. Adventures like The Extraction Job present encounters where the moral dimension is the challenge — the combat is straightforward, but deciding whether to fight at all is the real test. The Merchant’s Vault puts players in competition with rival thieves while revealing that their employer has been lying, turning what could be a simple combat encounter into a negotiation, a betrayal, or an unexpected alliance.

For small groups, these layered encounters are invaluable. They extend encounter length through decision-making rather than hit-point attrition, they reward the creative thinking that small groups excel at, and they produce the kind of memorable moments that players discuss long after the session ends.

Scaling Published Adventures for Small Groups

If you’re running a published module designed for four players, don’t just cut enemy count in half and hope for the best. Published adventures require thoughtful adaptation to work for small groups, and the process is faster than most DMs expect once you know what to change.

First, identify the encounters that matter narratively — the scenes that advance the plot, reveal information, or create memorable moments. These are your keepers. Cut or combine filler encounters that exist primarily for attrition. A published adventure with eight encounters should become three to four for a small group, using the three-encounter structure described above.

Second, replace multi-enemy encounters with single-enemy-plus-environment designs. If the module calls for six bandits, use two bandits and an unstable environment — a burning warehouse, a flooded cellar, a cliffside path with a long drop. The tactical complexity stays high while the action economy works for fewer players.

Third, add rest opportunities between encounters. Published modules often assume the party can sustain damage across six fights. A small group needs recovery time after every significant encounter, so insert short rest opportunities at natural narrative pauses. A barricaded room after clearing a corridor, a brief safe haven offered by a grateful NPC, or a simple passage of time between adventure locations.

Our Ready Adventure Series eliminates this adaptation work entirely — every adventure is designed for 2-3 players from the first draft, with encounter pacing, difficulty, and rest opportunities already calibrated for small groups.

Stop Calculating, Start Designing

The best encounters for small groups don’t come from a calculator. They come from DMs who understand that interesting environments, meaningful choices, and dynamic enemy behavior create better fights than correctly tabulated Challenge Ratings ever will.

Trust the principles over the math. Design environments first, enemies second. Give every fight a decision point that isn’t just “attack or don’t.” And remember that two or three invested players solving problems creatively will find more fun in a single well-designed encounter than a full party grinding through six forgettable ones.

Your small group isn’t missing players. Your encounters just need better design.

Every encounter tested for small groups. No rebalancing, no guesswork. Browse the Ready Adventure Series at anvilnink.com — adventures built for 2-3 players from the ground up.